Uncle Y Y Lee outside the house he was born in

A couple of things precipitated this blog post. First, I found a link from this Hainan Island related site.

Then I remembered that my uncle (father’s brother) didn’t attend my wedding because, as my cousin informed me a day before that, that he ‘couldn’t make it, because his leg cannot lah’, and how I thought it would have been nice for him and my dad to meet up, given that both of them are coming along in age, though at this time, I don’t want to say either of them is ‘ailing’.

I was a bit disappointed because I had even gotten Naomi to practice saying ‘Uncle, drink tea’ in Hainanese, after asking my father how to say ‘Uncle, drink tea’ in Hainanese.

It’s been a while since Part Three, and even longer since I was actually on the trip to the island of my forefathers.

The tour bus took us to Kachek town, and dropped us off at a 3-star hotel (so my cousin told me), but by this time, whatever stars that rated hotels on Hainan meant little as we checked ourselves into our rooms with the rock hard coconut husk beds.

After resting a bit in our rooms, my cousin made another phone call to the ancestral village to inform whatever relatives we had there that we had arrived. We were then told that ‘a few of them would be coming down to have coffee with us’.

I had never spoken to any of these relatives, much less known what they looked like, though I’ve been told that all Hainanese men look alike, and that every waiter at Shashlik looked like Dad, and Mum had previously told me that all Hainanese women looked like my grandmother. At 80.

But none of us expected a welcoming committee from the village, on a rickety hired bus, driving into the hotel’s car park and disembarking into the lobby, to ‘have coffee with us’. I think there were at least a dozen of them. At least they didn’t bring any coconut-related souvenirs, because by that time I had sworn off coconuts for life. It’s a bit hard to explain how pervasive the coconut problem is, but you’d get an indication reading the tourist information for the City of Wenchang, which begins like this:

Distinguished by the quality and quantity of its assorted coconut products, Wenchang City is a vital gateway to a lively area that contains some of Hainan Province’s most charming sightseeing and holiday destinations…

Coffee at the hotel’s lobby cafe, which also served all manner of coconut drinks, took a good two hours, with long conversations, mostly with the Hainanophone among us jabbering away, and with me nodding and smiling. My cousin later told me that my relatives were telling us about the sad state of my great grandfather’s grave, which, due to lack of maintenance, due to a lack of funds coming from the Lee family overseas, had been overrun by chickens from the free range chicken farm nearby.

The next morning, the rickety bus came to the hotel to fetch us to the village, this time, only six relatives served as entourage, and about an hour into the journey, we arrived at a dusty, non-descript township, where, upon the gutteral utterances of the driver (who was a cousin as well, I discovered) we disembarked and were led into a shophouse, where we were made to buy incense, hell-money and enough firecrackers to burn down a small town.

The township looked something like this: Dusty and unremarkable

Then bus driver-cousin said something, and my travelling-companion-cousin handed more cash over to him, and off we went to another shophouse, where more things were bought. All this while, of course, we had to keep my uncle from buying more coconut-related souvenirs.

Another half hour on the bus and on a dirt road where we passed several tiny villages with really old-looking buildings, we disembarked outside a little drinks kiosk-like building that had benches and a shelf that looked like it would have housed a television set. Bus driver-cousin and entourage-cousins beckoned for us to follow them behind the building, on a tiny footpath lined by trees. A five-minute trek later, we were in what looked like a little nook in the woods, with a cluster of buildings that made the place look like the set of ‘Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon’. It was that old.

We walked past a well with an electric motor pump, which my cousin said was the ‘running water’ that my Dad and uncle had donated money to the village for, and then we were guided through a courtyard and into a small house. On the wall were photographs of people who looked really familiar – and then I realised they were of my uncle and of Dad, taken some time in the 60s. Alongside those photos were those presumably of other uncles and cousins, though, like I’ve been told, you can’t really tell because all Hainanese men look the same.

A very distant cousin brings coffee mugs out of the house

A few chairs lined the walls, and we were asked to sit and wait as scores of people started streaming into the house, and according to my cousin, all of whom claimed to be a cousin or other. This was supposed to make us give them ang pow money or something. Some came, said a few words, took their share, and left, while others would come in, jabber away for a longer time, leave, and then come back again to say some more.

Uncles, aunts and cousins cram for a photo

Then a line of men came into the house, and I was told they were the village school’s teaching staff. Remembering that my Dad told me he donated money to build the village school, I asked to be taken to the school for a look. It was a pretty rundown two-storeyed building, and empty. Then one of the teachers showed me a few Peruvian nuevos soles from his wallet, and asked in Mandarin if they were American dollars. ‘South American’, I said, in Mandarin. He then insisted they were American dollars, because, he said, someone had exchanged them for a substantial amount of Renminbi with him.

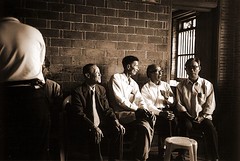

Uncle Y.Y. with the visiting schoolteachers

Then came time to visit great grandfather’s chicken overrun grave. Bus driver-cousin led the way via a series of footpaths, holding the long coil of firecrackers we had let him buy earlier. There was a small headstone which he dusted off, and we could make out our surname on it, and not much else. Not that it would’ve mattered, since neither of my travelling-companion cousins could read Chinese.

The thing about Great Granddad’s grave was that it was situated in sort of an open ground, sort of in between villages. It wasn’t in a cemetery proper, which probably explained the chickens running amok and flattening, over the years, the mound that distinguished a grave as a Chinese one.

The chickens were there when we got to the grave, but no matter, Great-Granddad was treated to the longest firecracker barrage I’d ever heard, and we returned to the house as soon as the smoke cleared, which was after we had stamped out the little brushfires that the firecrackers and burning hell notes started, but I think we were slightly pleased that the rogue chickens were probably scared shitless and deaf by now.

But one of my cousins was quite visibly disturbed, and she paused to ask why Great-Granddad was buried so near the house, to which I offered, ‘because last time no ambulance, people die already got no car to take them to the cemetery’. She seemed pretty satisfied with that explanation, which was good, because I was being eaten alive by mosquitoes at that point, and wanted to get out of the bush as soon as possible.

Back at the house, a feast was being prepared for the visiting Lees. This meant half the duck population in the village squawked their last as they were turned into the county’s specialty – boiled/steamed duck. The courtyard outside the house was set up with tables and stools, as we were taken indoors and shown the room which Uncle Y.Y. and my Dad were born in.

I was told how both Uncle and Dad had left Hainan at a very early age to look for Granddad in Malaya, leaving Grandma behind until she managed to find her way to Malaya via Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand.

There were stories of other cousins and uncles who left the island from the 1930s onwards, in a two-generation long diaspora that waned only recently, and probably ended with the reverse migration of several old Hainanese back to the village from Malaysia and Indonesia.

But food was served, steaming duck with the county’s other specialty – a yellowish chili sauce that was spicier than it looked. The feast was surprisingly good, although I remained a little unnerved by the number of villagers who stared and kept commenting how much I looked like Granddad and Dad.

After the meal, my cousin requested that we be brought back to Kachek town as it was getting late and that we didn’t want to keep them from doing their thing, seeing as it was a weekday and all. Of course, the villagers didn’t do much besides tending to the ducks and vegetables, whether it was a weekday or not, because most of the able-bodied members of the Lee clan had long since gone to the cities for work, leaving only the old and very young crouching and hiding about the village buildings.

Truth was, we were looking for clean toilets, and the amenities in the village would have been less than able to withstand the work of my weak stomach.

After we were dropped off back at the hotel, and goodbyes said (including a false promise of a return to the village the next day), we flagged a taxi and asked the driver to take us downtown, the Singapore-Malaysian-Hainanese word for which was different from the Hainanese-Hainanese word.

At the chicken slaughterhouse a few minutes outside downtown Kachek, the taxi-driver laughed his Hainanese head off when we explained that our word for ‘downtown’ sounded exactly like his word for ‘chicken farm’, and that we really didn’t want to have dinner there.

Having made his day, the taxi-driver very kindly took us downtown, to a street with many outdoor food stalls, where we had a dinner of fried noodles before my female cousin said she was going to look for a dessert that our late Grandma used to tell her about. Something called ‘Guay Dai Din’ in Hainanese, which translates to ”Chicken Shit’ Something’ in English.

She found it, this Chicken Shit Something, and ordered a large basin of sweet syrup filled with black starch pellets, to share with all of us. It wasn’t half bad, this dessert, and I think it would’ve made it to Southeast Asian Hainanese kitchens and restaurants if it wasn’t saddled with such a marketing problem.

The next day, the tour van came back and picked us up for the long drive back south to Sanya, where we were treated to more coconut-related tourist spots before finally boarding the charter back to Kuala Lumpur, with a hundred odd Hainanese pilgrims carrying a load of coconut by-products and many, many stories of the home country.

Technorati Tags: china, hainan

in hainanese, uncle, drink tea is… ‘boh deh, jia ___’ i dont know how to say tea in hainanese.. anyway im hainanese too and been trying to speak more hainanese…. not many people know how to speak!

My mum and my aunt have been going back to Hainan on and off for the past few years, but I haven’t had the time or opportunity to return. I speak Hainanese quite well (I was brought up by my grandmother till secondary school) and hope to return one day to connect with my roots.

I’m Tony Tan from Malaysia. I have visited Hainan Island a few times already taking flights from KL direct to Hainan. I will be going to Hainan Island again on the 23rd of August, 2011 but this time from S’pore Tiger Airway as AirAsia no longer fly to Hainan Island. I intend to make Hainan Island my second home. Would like to keep in touch with hainanese people from around the world.

(Just curious: For a malay who can speak hainanese is just fanatastic. My son is 100% hainanese but sad to say can’t speak hainanese fluently.)

hey,Tony,Im Stan wan,a boon sio man,fr kl.Please highlight ur experience on this coming trip,ok.Mybe,Im planning a holiday there too.But Ive forgotten my roots there.Only or visits,Tq.Happy holiday.

Dear Stan Wan,

Sorry for the late reply. Since you can speak hainanese quite well I don’t think you have forgotten your roots. Ask your mum, your aunt, your mum’s relatives in Hainan village, or check with the local hainan association.

If you are still single, go back to the village and marry a local hainanese girl and bring her back to Malaysia. They make very good wife and know how to use washing machine and electric iron, but first must send them to our local obedient wife club for training first.

Let me know when you want to go to Hainan Island. Maybe I can meet you there. For my August trip, my aunty and daughter, my cousin and his wife and son is coming along. I have told my cousin in Hainan to get ready at least a hundred feet long fire crackers to announce our home coming. You will also get the same treatment if you go back to your ancestor home. The chicken that they cook for you are kampung chicken (no hormone). Keep in touch Stan and God bless.

Great to encounter so many oversea born hainanese (wa-kiao) here. My dad and his generation visit hainan often, and I have been holding off probably because of some rebelling against the noisy older folks. However, a strong contingent of our family member will be finally visiting our ancestral home this Nov. OoLong Sui, WenChang. Whenever we hainanese meet each other, there is this certain bond, perhaps being able to communicate in the dialect. My other friends could not understand us and refer to us as Germans. I have met Indian speaking hainanese at very old restaurant such as at Coliseum KL and Terengganu.

in hainanese, uncle, drink tea is… ‘boh deh, jia ___’ i dont know how to say tea in hainanese.. anyway im hainanese too and been trying to speak more hainanese…. not many people know how to speak!

lol. yeah. not many people knows how to speak hainanese. especially youngsters. i think in future it might even extinct. i, myself is also one, who rarely speaks it. the problem often faced is we know what they are talking but dont know how to respond.

lol. yeah. not many people knows how to speak hainanese. especially youngsters. i think in future it might even extinct. i, myself is also one, who rarely speaks it. the problem often faced is we know what they are talking but dont know how to respond.

Ah Hainan, land of crazy people.

Ah Hainan, land of crazy people.

i can only speak hainanese when i was 3 years old :p

i was born there.

but after i moved to HK, 3 months later i could only speak cantonese …

i can only speak hainanese when i was 3 years old :p

i was born there.

but after i moved to HK, 3 months later i could only speak cantonese …

Really enjoyed reading this Mr M.

Really enjoyed reading this Mr M.

tea in hainanses is ‘teh’ but it sounds different from the hokkien ‘teh’. instead of going up, the tone towards the end goes down. hope i’m making sense heh

nice reading your post miyagi… reminds me of the time when i went back alone to my grandfather’s village. he was from wenchang too

tea in hainanses is ‘teh’ but it sounds different from the hokkien ‘teh’. instead of going up, the tone towards the end goes down. hope i’m making sense heh

nice reading your post miyagi… reminds me of the time when i went back alone to my grandfather’s village. he was from wenchang too

Omg, the mother never told me those stories. Love the pics, really special.

Omg, the mother never told me those stories. Love the pics, really special.

I really like the pics!

*clap clap*

I really like the pics!

*clap clap*

I am half-Hainanese. Drink tea is “Jia leyh.”

“Jia leyh coo baw?”

I am half-Hainanese. Drink tea is “Jia leyh.”

“Jia leyh coo baw?”

i’m hainanese too. really enjoy reading all your posts on the heritage.

i’m hainanese too. really enjoy reading all your posts on the heritage.

It’s actually deh3 (think hanyu pin yin). Being brought up by my only-can-speak-hainanese-grandparents, I’m pretty proud to say I can converse with my grandfolks’ generation without a hitch.

It’s actually deh3 (think hanyu pin yin). Being brought up by my only-can-speak-hainanese-grandparents, I’m pretty proud to say I can converse with my grandfolks’ generation without a hitch.

ah kor..

the ‘chicken shit something’, can be found in certain hainan eating places in singapore. i think somewhere on the east side.

my parents claim it prevents cancer. they eat it almost everyday. can’t remember where my mum gets the veggie from. apparently plucked from somewhere. she swears it’s the real thing.

my grandfather was from Wenchang too, my ancestral village is baofang village.

and yes, most hainan island men do really look alike. it’s still very much the wild wild west of the china, or south rather, as you have captured with your pic of the township. pretty much left behind while the rest of coastal china speeds along in progress and consumerism.

apparently one of my ancestors was some military officer who fought in some war..which kinda explains my snarling satisfaction at the sound of ‘first blood!’.. o_O

ah kor..

the ‘chicken shit something’, can be found in certain hainan eating places in singapore. i think somewhere on the east side.

my parents claim it prevents cancer. they eat it almost everyday. can’t remember where my mum gets the veggie from. apparently plucked from somewhere. she swears it’s the real thing.

my grandfather was from Wenchang too, my ancestral village is baofang village.

and yes, most hainan island men do really look alike. it’s still very much the wild wild west of the china, or south rather, as you have captured with your pic of the township. pretty much left behind while the rest of coastal china speeds along in progress and consumerism.

apparently one of my ancestors was some military officer who fought in some war..which kinda explains my snarling satisfaction at the sound of ‘first blood!’.. o_O

I will find some ‘chicken shit something’ at lunch one of these days. BTW, my family’s not from Wenchang City, they’re from near Kachek, which is in Henghai (Qionghai) County. In the northeast. Or so they tell me.

I will find some ‘chicken shit something’ at lunch one of these days. BTW, my family’s not from Wenchang City, they’re from near Kachek, which is in Henghai (Qionghai) County. In the northeast. Or so they tell me.

Gorgeous pictures. Were they taken by you?

Gorgeous pictures. Were they taken by you?

Im Hainanese too.

Tea shd be more like ‘dae-er’

I m not sure abt ‘jia’ – literally, eat tea … shd be more like ‘sweh dae-er’

Heh heh, I thot Hainan Island is where if the Emperor dun like u, u get banished there. [LOL]

Im Hainanese too.

Tea shd be more like ‘dae-er’

I m not sure abt ‘jia’ – literally, eat tea … shd be more like ‘sweh dae-er’

Heh heh, I thot Hainan Island is where if the Emperor dun like u, u get banished there. [LOL]

great post, loved the pictures and i was chuckling at the pc in the office reading it!

great post, loved the pictures and i was chuckling at the pc in the office reading it!

A little something from me for the enjoyment of everyone, especially fellow Hainanese:

http://hutdugaikarsui.blogspot.com/2006/03/comic-with-hainanese-dialogue.html

http://hutdugaikarsui.blogspot.com/2006/09/just-comic-04-epilogue.html

A little something from me for the enjoyment of everyone, especially fellow Hainanese:

http://hutdugaikarsui.blogspot.com/2006/03/comic-with-hainanese-dialogue.html

http://hutdugaikarsui.blogspot.com/2006/09/just-comic-04-epilogue.html

hey, how interesting. My grandparents came from some village in Wenchang, Hainan too (perhaps our grandparents know each other; you’d never know ;p). I went to Wenchang (Hainan) with my family 5 years ago and my dad was looking for a relative with the surname Fu. Imagine his surprise when he’s told that almost everyone has that surname in that particular village. [since then our family has visited our relatives a few times].

[since then our family has visited our relatives a few times].

I happened to be able to speak Hainanese so it’s really delightful that they understand what I said to them

I agree with BondX that ’sweh dae-er’ is ‘drink tea’ in Hainanese.

hey, how interesting. My grandparents came from some village in Wenchang, Hainan too (perhaps our grandparents know each other; you’d never know ;p). I went to Wenchang (Hainan) with my family 5 years ago and my dad was looking for a relative with the surname Fu. Imagine his surprise when he’s told that almost everyone has that surname in that particular village. [since then our family has visited our relatives a few times].

[since then our family has visited our relatives a few times].

I happened to be able to speak Hainanese so it’s really delightful that they understand what I said to them

I agree with BondX that ’sweh dae-er’ is ‘drink tea’ in Hainanese.

I’m hainanese too. A pleasant surprise that one of the frequent bloggers that I’m reading about is Hainanese too.

I’m hainanese too. A pleasant surprise that one of the frequent bloggers that I’m reading about is Hainanese too.

WOW!What a great read.

My grandparents practically raised me and my bro and I swear we spoke Hainanese like pros… whonder what happened.

Went to look for my roots on Hainan Island too when I was a kid. The most vivid memory I have of that: stepping on a praying mantis while half asleep. Yup, I just goofed it up.

Love your pictures!

WOW!What a great read.

My grandparents practically raised me and my bro and I swear we spoke Hainanese like pros… whonder what happened.

Went to look for my roots on Hainan Island too when I was a kid. The most vivid memory I have of that: stepping on a praying mantis while half asleep. Yup, I just goofed it up.

Love your pictures!

I married to a hainanese men. A very good husband. We plan to visit our in-laws hometown (Wenchang – Mai Hao) this coming school holiday. Been looking for more informations about Hainai Wenchang esp the small town.

Your blog is unique and I also love the black and white pictures.

I married to a hainanese men. A very good husband. We plan to visit our in-laws hometown (Wenchang – Mai Hao) this coming school holiday. Been looking for more informations about Hainai Wenchang esp the small town.

Your blog is unique and I also love the black and white pictures.

Dear Ah Kor

I too went back to Hainan island for the first time in November last year and my home village was near Hai Kou in Wenchang area in a district called Foal Tai. Reading your blog brings back memories of the vist with my father. I brought my kid along as well and I actually spent a night in the ancestral home and enjoyed speaking to my cousins and uncles in hainanese that I learnt from my parents and grandparents.

We also took in a tour of the whole island and visited places that you did including the Botanic gardens, hot springs, Southern mountain with a 1500 year old Buddhist temple and 5000 grave mounds sprinkled on the mountain, ate the Wenchang chicken and the Kachek duck, visited Charlie Soong’s ancestral home….yes the father of the famed Soong sisters was hainanese.

Also saw Hai Rui’s tomb that was vandalised during the Cultural Revolution because the event that triggered the Cultural Revolution was a play about Hai Rui. Apparently the play was about Hai Rui (loyal prime minister and his despot tyrant of an emperor) and his emperor …the play was seen as an oblique reference to Mao Tse Tung.

Enjoyed your Hai Nan trip blog very much. Cheers

Dear Ah Kor

I too went back to Hainan island for the first time in November last year and my home village was near Hai Kou in Wenchang area in a district called Foal Tai. Reading your blog brings back memories of the vist with my father. I brought my kid along as well and I actually spent a night in the ancestral home and enjoyed speaking to my cousins and uncles in hainanese that I learnt from my parents and grandparents.

We also took in a tour of the whole island and visited places that you did including the Botanic gardens, hot springs, Southern mountain with a 1500 year old Buddhist temple and 5000 grave mounds sprinkled on the mountain, ate the Wenchang chicken and the Kachek duck, visited Charlie Soong’s ancestral home….yes the father of the famed Soong sisters was hainanese.

Also saw Hai Rui’s tomb that was vandalised during the Cultural Revolution because the event that triggered the Cultural Revolution was a play about Hai Rui. Apparently the play was about Hai Rui (loyal prime minister and his despot tyrant of an emperor) and his emperor …the play was seen as an oblique reference to Mao Tse Tung.

Enjoyed your Hai Nan trip blog very much. Cheers

Thanks for reading! Your trip sounds really enjoyable too.

Thanks for reading! Your trip sounds really enjoyable too.

Your trip sounded exactly like my family’s whenever we return to Hainan (I am 3/4 hainanese (boon-sioh x2, ka-chiek x1), 1/4 hokkien but very proud of my hainanese roots). Just thought I’d mention something – My granduncle who lives in Malacca rang us excitedly one evening to tell us that the current PM of M’sia (Abdullah Ahmad Badawi) is half hainanese-chinese.

Your trip sounded exactly like my family’s whenever we return to Hainan (I am 3/4 hainanese (boon-sioh x2, ka-chiek x1), 1/4 hokkien but very proud of my hainanese roots). Just thought I’d mention something – My granduncle who lives in Malacca rang us excitedly one evening to tell us that the current PM of M’sia (Abdullah Ahmad Badawi) is half hainanese-chinese.

Thanks alot for the info. I will move to Haikou soon, guess its true about there being so many hainan expats.

regards

tommckay1478@hotmail.com

Thanks alot for the info. I will move to Haikou soon, guess its true about there being so many hainan expats.

regards

tommckay1478@hotmail.com

My dad is Hainanese, but has never spoken the dialect with me. My grandpa died before I was born, and I never got to converse with my granny whom I saw once a year and who has also passed away. It’s all very sad. Apart from knowing my roots are in Hainan Island, I don’t know anything else. No ancestral village, no relatives, nothing. It’s quite depressing not knowing where you came from.

My dad is Hainanese, but has never spoken the dialect with me. My grandpa died before I was born, and I never got to converse with my granny whom I saw once a year and who has also passed away. It’s all very sad. Apart from knowing my roots are in Hainan Island, I don’t know anything else. No ancestral village, no relatives, nothing. It’s quite depressing not knowing where you came from.

I visited my ancestral home some twenty years ago. We tour the island while the red guard was creating turmoil in Bejing. It was at the peak of the so call cultural revolution. The local TV did not reveal much. I managed to follow the event on BBC short wave. My ancestral village is linked to Kachek City, Is called “Shum Tua” farm head.

I visited my ancestral home some twenty years ago. We tour the island while the red guard was creating turmoil in Bejing. It was at the peak of the so call cultural revolution. The local TV did not reveal much. I managed to follow the event on BBC short wave. My ancestral village is linked to Kachek City, Is called “Shum Tua” farm head.

Hi

I read your site cos my mum pass on last year and I thought I’d go visit the place she was born in Wenchang and maybe write a book in the future – a record for her grandchildren. I was wondering if it is too touristy? Im a seasoned backpacker and would like to make the trip this october. Do u think the local transport is efficient?

You blog was a good read. Tks.

Cheers

Hi

I read your site cos my mum pass on last year and I thought I’d go visit the place she was born in Wenchang and maybe write a book in the future – a record for her grandchildren. I was wondering if it is too touristy? Im a seasoned backpacker and would like to make the trip this october. Do u think the local transport is efficient?

You blog was a good read. Tks.

Cheers

Hi Chiau, No I don’t think Wenchang’s too touristy, though places like Sanya might be. Local transport is um… patchy at best. Best to get a tour package and pay the driver extra to point you to places. Then again, that was 2002, and things might be a bit different now.

Hi Chiau, No I don’t think Wenchang’s too touristy, though places like Sanya might be. Local transport is um… patchy at best. Best to get a tour package and pay the driver extra to point you to places. Then again, that was 2002, and things might be a bit different now.

I went to Hainan in March’07. The places I’ve visited are Haikou, Sanya, Wenchang, Qiong Hai and WanNing. The beaches in Sanya are really nice, with fine sand and water crystal clear. Shopping open till 11pm. Food and fruits are really cheap. For my friends who are non-Hainanese, they had no communication problem because Mandarin is a common spoken language in the island. Definitely, I’ll visit the place again.

I went to Hainan in March’07. The places I’ve visited are Haikou, Sanya, Wenchang, Qiong Hai and WanNing. The beaches in Sanya are really nice, with fine sand and water crystal clear. Shopping open till 11pm. Food and fruits are really cheap. For my friends who are non-Hainanese, they had no communication problem because Mandarin is a common spoken language in the island. Definitely, I’ll visit the place again.

Im hainanese too! Unfortunately, i can only say ‘jiat buay’… Im so embarrassed about not being able to speak my dialect and the loss for words when communicating with my only grandmother. Im looking for hainanese lessons.. so if anyone out there have any lobangs, please contact me! @ jay_wmd88@hotmail.com OH ya, nice pics, brought me back to 10 years back when i was visiting my grandpaps in his village. Dang it was fun, with the shooting of chickens and etc.

Im hainanese too! Unfortunately, i can only say ‘jiat buay’… Im so embarrassed about not being able to speak my dialect and the loss for words when communicating with my only grandmother. Im looking for hainanese lessons.. so if anyone out there have any lobangs, please contact me! @ jay_wmd88@hotmail.com OH ya, nice pics, brought me back to 10 years back when i was visiting my grandpaps in his village. Dang it was fun, with the shooting of chickens and etc.

Shooting chickens? Why on earth would you need to shoot chickens? Oh wait. Yah, Hainanese.

Shooting chickens? Why on earth would you need to shoot chickens? Oh wait. Yah, Hainanese.

you take a lot of nice picture i like it alot…recently i am going to open a hailam cafe in kl can i use some of the pic you have shoot

you take a lot of nice picture i like it alot…recently i am going to open a hailam cafe in kl can i use some of the pic you have shoot

Hi Ah Kor,

Just came back from the beautiful island of Hainan, to look for my roots in the province of Qionghai, where Kaichek is the main city. Food and lodging were cheap compared to Singapore. Had a breakfast meal of 6RMB (about S$1.50), and lunch at a restaurant is about 100RMB (S$20) for four pax.

And if you want hotel lodging lobangs in Kaichek or Haikou, and lessons in Hainanese, please look for me (suankhim@hotmail.com), can introduce you to some of the hotels (cheap and good, and most of all centrally located). In addition, I travelled via Kaicheck / Haikou to/fro via the public express bus (25RMB). Been touring the island with tour groups twice since 2006, and I am most impressed with the Nan Hai Kuan Yin (also known as Nan Shan). The image is simply beautiful, and the scenery is most impressive, it is most serene just looking at the image and the sea.

Hi Ah Kor,

Just came back from the beautiful island of Hainan, to look for my roots in the province of Qionghai, where Kaichek is the main city. Food and lodging were cheap compared to Singapore. Had a breakfast meal of 6RMB (about S$1.50), and lunch at a restaurant is about 100RMB (S$20) for four pax.

And if you want hotel lodging lobangs in Kaichek or Haikou, and lessons in Hainanese, please look for me (suankhim@hotmail.com), can introduce you to some of the hotels (cheap and good, and most of all centrally located). In addition, I travelled via Kaicheck / Haikou to/fro via the public express bus (25RMB). Been touring the island with tour groups twice since 2006, and I am most impressed with the Nan Hai Kuan Yin (also known as Nan Shan). The image is simply beautiful, and the scenery is most impressive, it is most serene just looking at the image and the sea.

99.9 percent Hainanese are sohai’s , Nang bo dee Nang, Gui bo dee gui

Nick Cheong, I think you need your head to be examine for such stupid remarks. I think the biggest fool is you but you did not realise it.

Nickcheong , i think you need a thorough examination of your brain ,

you seem to be a ” sohai’s ” yourself : head without brain.

99.9 percent Hainanese are sohai’s , Nang bo dee Nang, Gui bo dee gui

hi guys, where can i find hainanese restaurant in Singapore?

hi guys, where can i find hainanese restaurant in Singapore?

Just return from Hainan today from Wechang, Sia Liang Chun (ancestral home), stayed there for 1 week and slept in the room that my grandparents lived and saw my 1st ancestral tomb just outside the house.

Just return from Hainan today from Wechang, Sia Liang Chun (ancestral home), stayed there for 1 week and slept in the room that my grandparents lived and saw my 1st ancestral tomb just outside the house.

Hey thanks for the comment on my blog at: http://blogist.wordpress.com/2008/04/03/lands-end-chicken-poop-dessert/

I added more photos to illustrate how the “Kwei Tai Din” and “Kwei Tai Bwa” comes from.

Btw, I’m 18 this year and went back to Kachek alone just a week ago. hehe. My grandpa’s village is at Qionghai, Wenquan. Jinpo Village.

Hey thanks for the comment on my blog at: http://blogist.wordpress.com/2008/04/03/lands-end-chicken-poop-dessert/

I added more photos to illustrate how the “Kwei Tai Din” and “Kwei Tai Bwa” comes from.

Btw, I’m 18 this year and went back to Kachek alone just a week ago. hehe. My grandpa’s village is at Qionghai, Wenquan. Jinpo Village.

Hi, just got back from Hainan 3 days ago, went to my grandparents home town at Xionghai, kaichek, Gu kwou Sui, surname Lee. Just need some info. as to why many of those left QiongHai in haste, with stories of fights/killing & most of the older folks have fears of returning to their villages. Are the fight among communist & Koumingtang? I cldn’t understand what my late granny said when she refers those period as difficult time…Anyone know?

Hi, just got back from Hainan 3 days ago, went to my grandparents home town at Xionghai, kaichek, Gu kwou Sui, surname Lee. Just need some info. as to why many of those left QiongHai in haste, with stories of fights/killing & most of the older folks have fears of returning to their villages. Are the fight among communist & Koumingtang? I cldn’t understand what my late granny said when she refers those period as difficult time…Anyone know?

Btw, I was taught that drink tea is ” cheak deh”…

Btw, I was taught that drink tea is ” cheak deh”…

hi…

my name moko…jia qi(chinese)…but dunno in hainanese hehe

i can’t speak hainam, may just few words…but my father knows hainanese lil’ coz my grandpa died when my father was child..

any one know how i can learn hainam?? or hainam dictionary??

boh kai..

i don know why but i wanna find out bout hainam this lately..bout people, may how they live there?? it’s like that you can give me a real atmosphere in hainam hei…(may it’s the only me, coz i like a photograph)

i donno my granpa also has a related of communist & Koumingtang, so he has been chased in hainam before(he told that to my father before he died)…and that’s a really2 tough time that time..

for mr.miyagi, i really love your posting about hainam, coz i never visit there…:(

hehe…keep posting bro…thank you very much

hi…

my name moko…jia qi(chinese)…but dunno in hainanese hehe

i can’t speak hainam, may just few words…but my father knows hainanese lil’ coz my grandpa died when my father was child..

any one know how i can learn hainam?? or hainam dictionary??

boh kai..

i don know why but i wanna find out bout hainam this lately..bout people, may how they live there?? it’s like that you can give me a real atmosphere in hainam hei…(may it’s the only me, coz i like a photograph)

i donno my granpa also has a related of communist & Koumingtang, so he has been chased in hainam before(he told that to my father before he died)…and that’s a really2 tough time that time..

for mr.miyagi, i really love your posting about hainam, coz i never visit there…:(

hehe…keep posting bro…thank you very much

Hello Miyagi,

You downplay hainan as an underdevelop pieces of shit and it is not fair. I have been to Hainan in 2003, 2005, 2007. We were welcome with biggest hearts that is the hainese in hainan that I have never seen in my life. Children lining up in the sun rows over rows miles upon miles to welcome us. Where every we go there is always a military personal with us. Everywhere we go the Hainanese delegate from Hainan is there to received us. Even when my Uncle and I went to Wenchen at the ancestrial village the Major of Wenchen excorted us there. Hainan is very beautiful even words could not describe it . Especially at Sanya while soaking oneself in the hotsprings one could image as a fairy desending from heaven enjoying the comfort. I will be going back to Hainan again in November 2009. I have travel everywher in the world it is Hainan that I always to back to.

See you again in Hainan

Marina Burn

Hello Miyagi,

You downplay hainan as an underdevelop pieces of shit and it is not fair. I have been to Hainan in 2003, 2005, 2007. We were welcome with biggest hearts that is the hainese in hainan that I have never seen in my life. Children lining up in the sun rows over rows miles upon miles to welcome us. Where every we go there is always a military personal with us. Everywhere we go the Hainanese delegate from Hainan is there to received us. Even when my Uncle and I went to Wenchen at the ancestrial village the Major of Wenchen excorted us there. Hainan is very beautiful even words could not describe it . Especially at Sanya while soaking oneself in the hotsprings one could image as a fairy desending from heaven enjoying the comfort. I will be going back to Hainan again in November 2009. I have travel everywher in the world it is Hainan that I always to back to.

See you again in Hainan

Marina Burn

Good for you Marina. I didn’t get the organised mayoral welcome nor the military escort. I must have had the wrong travel agency :).

Good for you Marina. I didn’t get the organised mayoral welcome nor the military escort. I must have had the wrong travel agency :).

this is a really interesting trip. I have enjoyed reading and I'm planning a similar trip next year.

Nice blog!

do you think this place would be ideal for backpackers too?

Is road accessible?

thanks!

More of my backpacking Online Journal;

http://cheapbackpackertravel.com/

Hi Miyagi,

I am a French student preparing a thesis on Hainan, and I really enjoyed reading your trip report. Are there many Oversea Hainanese from Malaysia and Singapore visiting their ancestral village ?

I would like to know more about the Oversea Hainanese and their relations with Hainan

Hi Miyagi,

I am a French student preparing a thesis about Hainan. I enjoyed reading your trip report. Are there many oversea Hainanese from Malaysia and Singapore visitng their ancestral village ? I would like to know more about the relations between Oversea Hainanese and Hainan.

YOU are lucky.. THe old house is still in usable condition.

My dad's house is partly ruin. One third damaged to the ground since Japanese invasion 70yrs ago. The other 60%, intact except for the roof. The paddy lands confiscated by communists lords. The vacant lands grab by neighbours and relatives with better contacts with dept concened. Grandpa murdered during Gang of Four revolution and grand ma survived almost alone. All assets grab by all concerned.

We visited 2-3 times.

Previously, we were told to rebuild the house. Now, we were told no need to. I am suspicious that they want to grab the house too.

Do they have land title office there to confirm ownership?

Is it costly to rebuild a house?

Hello Shaolin Tiger,

This is a racial slunr. Please check us up with the world famous chinese, the answer speaks for it self.

Marina Burn

Hello Steve Lim.

Overseas Hainanese are allow to file for return of all Land and properties conficasted by the government. You have to go thro your local Hainanese asssociation where ever you are and make inroad connection to the local county in Hainan for the claim.

Marina Burn

Hi Marina ,when you refer to local Hainanese asssociation in china or others country

local Hainanese asssociation.

If you are unable to reply here..email me at jurongmail@yahoo.com.sg

Like to real proof that all ancestor spring is allowed to claim back their land as proof by their relative or villages head.

I came back from Hainan Wencheng got the endorsed document land under my name…share with you ,my parent never went back for 100 years and the house was still standing but of course some wall had missing..is ok.

You need to do 2 thing to claim.

Drop me a email at jurongmail@yahoo.com.sg

I direct you which department to get your encestors land endorse under your name is ‘free of charge but of course some mean of red gift ..not bad as less as Yuan $500″

Do not believe ..someone ..actually you can do it yourself .

The posted above yuan is a fee pay to the department as for me …free of charge.I just want to help…I understand you will go through all the hightmare,worries on how to claim your ancestor home…No fee from me,just want to help.

RE: That’s interesting Marina. Would be amazing if it were possible. http://tinyurl.com/lx8edk

That's interesting Marina. Would be amazing if it were possible.

That's interesting Marina. Would be amazing if it were possible.

I am born and bred in Malaysia…. 1st generation Chinese. Both my parents were from China. They were married there and then migrated to Malaya in the early 1950s.

My ancestors were from the gentry class and therefore owned lands. I actually claimed a piece of land in the village that was confiscated by the communists. China under Chairman Deng allowed us to make the claims. My cousins and relatives in Malaysia subsequently did the same and they got back small plots enough to build a reasonable big house. In 1994, I built a house in my ancestral village. In 1998, we brought back dad’s remains (he died in 1987) to be buried in the family’s cemetery. All in all, I have been to Hainan for more than 30 times since 1991 as most of my parents’ siblings and families are there. For more info, my email….. wanglcster@gmail.com

My father and mother both from Hainan wenchang and my parent move to Singapore born me the youngest son and other 7 children.

My father had a land with house in wenchang and can anyone tell me ,how can I acquire the land transfer to my name.

The last time my sister went there and was told only son is permitted to own…I need more information on the department direction before I travel there to meet them..thanks for your kind help.

Can you tell me .where should I go to which government department for Overseas Chinese ancestor spring to Acquisition of Land Title in Hainan island -Wencheng,

There is no such department

Those day ,Yes! there no such department and even my parent don’t even have a birth certificate or ID but only proof meant by Domestic relative.

I had friends Acquisiton land by this way ,just want to know the new department might call Land registry department or something else.

ANYONE know care to let me know,thanks.

Dude, it’s a scam. There is no such thing

My grandparents has an old house at Wenchang. There is a Land/House Certificate. This very old Certificate has the names of the owner/inheritor. My Grandfather, Granduncle and My two 1st born aunts names are in it even though they were infant at that time. Try searching for this Certificate. For us, we are leaving the house/land to the present occupants who are distant relatives. The house is not comfortable for us to reside in and we stay at hotel during our visits.

My father was born in Hainan in 1904..do you refer to the same age as this years..how about your grandparents time?

My grandparents were born in the 1900-1915 period and migrated to Msia in the 1930s during/after the massive flood in Wenchang. The house/land certificate was still kept by the relatives who stay in the ancestral house. My mom referred to it as Land geran. Geran is the Malay word for title. Referring to Wang LC mail below, I do think you have a chance to claim. But do be careful of China middle man who claim they can do wonders.

No you can’t claim and anyone in China who says you can are lying to you. Please be careful.

Thanks Bo Jiang,I believe this generation of Chinese people are more educated.I went to some part of China and really love China,the people and especially the weather is cool.

The Chinese govt had make clear that overseas folk are allowed to claim their ancestral house..is being till now.

Many came back to Wencheng businessmen of Thailand,Hong Kong ,Singapore & Malaysia rest of Asia overseas folk had make this place to be a environmental investment for others part ,tourist attraction as a whole of welcome area.

There is nothing impossible in China now.!

I would like to bring poly students to Hainan to visit primary school or orphanage, for community service. Do you have any contacts? Thanks!

I am on leave . pls email to sng.sophia@gmail.com